The Way to the West: Kit Carson (Historical Reprint)

Historical article reprinted from the book "The Way to the West and the Lives of Three Early Americans: Boone, Crockett, Carson" written by Emerson Hough in 1903.

In reviewing the life of Christopher Carson, one of our Western leaders in exploration, we come upon the transition period between the time of up-stream transportation and that which led across the waters; the epoch wherein fell the closing days of Western adventure, and the opening days of a Western civilization. Kit Carson, as he was always called, was born in Madison County, Kentucky, on December 24, 1809.

Carson’s life rounds out the time of the great Westerners. He comes down to the railroad-building day. His was the time of the long-haired men of the American West. John Colter, Jim Bridger, Bill Williams, Beckwith or Beckworth; the great generals of the fur trade, Lisa, Ashley, Henry, Smith, Sublette, Fitzpatrick, all that company of the great captains of hazard—these were the men of his day; and among them all, not one has come down to us in more distinct figure or with memory carrying greater respect.

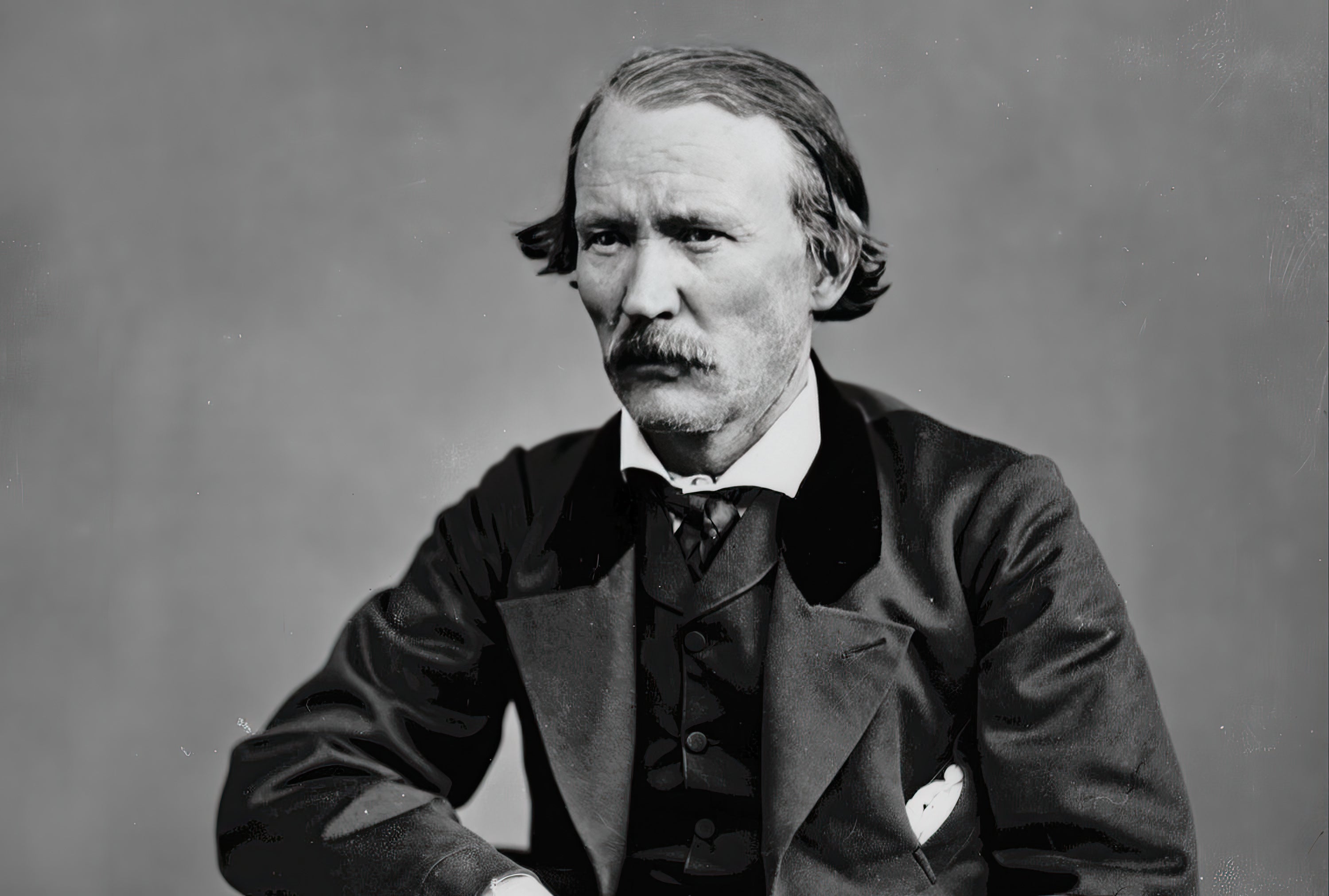

We call Frémont “The Great Pathfinder,” and credit him with the exploration of the Rockies, the Pacific slope, and the great tramontane interior basins. Yet Frémont did not begin his explorations until 1842, and, by that time, the West of the adventurers was practically an outlived thing. For ten years the fur trade had been virtually defunct. For more than a decade the early commerce of the prairies had been waning. The West had been tramped across from one end to the other by men peerless in their daring, chief among whom might be named this little, gentle, blue-eyed man, of whom that genially supercilious, and generally ignorant, biographer, J. S. C. Abbott, is good enough to write: “It is strange that the wilderness could have formed so estimable a character!”

This little man- he is described by one who knew him as a small man, not over five feet six inches in height- had, long before he ever heard of Frémont, ridden and walked along every important stream of the Rocky Mountains; had journeyed across the “American Desert” a dozen times, back and forth; had seen every foot of the Rockies from the Forks of the Missouri to the Bayou Salade; had seen all of New Mexico; had visited old Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California as we now know them; had camped at every resting ground along the Arkansas and Platte; had fought and traded with every Indian tribe from the Apaches up through the Navajos, Cheyennes, Comanches, Sioux, and Crows; had even fought the Blackfeet, redoubtable Northern warriors.

Five feet six, with twinkling blue-gray eyes, a large and well-developed head, with hair sandy and well brushed back, Kit Carson at his best was the reverse of impressive. He was simple, peaceable, and quiet in disposition, temperate and strictly moral in a time and place where these qualities made one a marked man. Yet throughout the length and breadth of the Indian country this little man was more feared, single and alone, than any other trapper or Indian fighter in all the West. He was respected as well as feared. One who knew him well said: “Carson and truth mean the same thing. He is always the same, gallant and disinterested. He is kind-hearted and averse to all quarrelsome and turbulent scenes. He is known far and wide for his sober habits, strict honor, and great regard for truth.”

In the garb habitual with him for more than half his life, Carson was clad in a fringed buckskin shirt, with leggings of the same material, also befringed. The shirt was handsomely embroidered with quills of the porcupine, and as much might be said for the moccasins that protected his feet. His cap was of fur, sometimes of fox skin, sometimes of raccoon skin, mayhap in days of great prosperity, of otter.

His rifle was that of Boone or Crockett, improved only to a limited extent, though carrying a ball somewhat larger than that needed in the forests of Kentucky. Otherwise, he might have been the typical early American rifleman of the Alleghanies. Under his right arm rested his powder horn and bullet pouch. A heavy knife for butchering hung at his belt, as well as a whetstone to keep it in good condition. At a certain time in his career Carson wore an ornamented belt, with heavy silver buckle, which supported two revolvers and a knife.

He took on, in modest sort, the picturesque fashions of the wilderness, and, uniting as he did the mountains and the plains in his habitat, at times showed something of the Spanish love of display in the trappings of his horse. His saddle and bridle had trace of Mexico in their gold and silver ornamentation. His horse, be sure, was a good one; for those were times when a man’s safety much depended on the fleetness and soundness of his mount, and the horse was the means of transportation for Carson and his kind.

As to the career of this Western man, if we come to follow it out as it occurred in sequence, we shall arrive at but one conclusion, to wit: that, conditions considered, Kit Carson was the greatest of all American travelers. It is almost unbelievable, the distances he traversed along with his wild fellows during those vivid years in which he forced the wild West to yield him a living. We cannot do better than to trace some of his wanderings, more especially those that occurred before the day of the so-called exploration of the West.

Frémont, who knew Carson well, speaks of him as a native of Boone’s Lick County, Missouri; but Doctor Peters, his biographer, states, apparently with Carson’s authority, that Carson was born in Madison County, Kentucky, as above stated, and while but one year of age was brought to Howard County, Missouri, by his parents. The father of Carson was a good farmer, according to the lights of his time, and a good hunter, the life of Missouri during those early times being practically that known by the blockhouse farmers of Kentucky in the time of Boone. Kit grew up sturdy, quiet, self-contained, self-reliant. In his boyhood he was a steady rifle shot, and early acquired a reputation. He “hunted with the Sioux Indians,” we are told, when yet a boy, which means he must have gone north up the Missouri.

At fifteen years of age, he was called “old for his age;” he was known to be plucky, prompt, and tenacious of his rights, though not in the least quarrelsome. Just as well-meaning parents tried to send Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone to school, so did the kind parents in this case undertake to instill commercial principles into the mind of Kit Carson. To his father it seemed important that he should be apprenticed to a saddler. From the saddler’s stool Kit promptly fell off. It was the outdoors that appealed to him; the West that spoke to him, just as it had to Boone and Crockett. He broke his heart for two years at the saddler’s bench, and that ended both his commercial and scholastic education. In 1826, while still but a boy, he was off and away across the plains, having, without his parents’ consent, joined a party bound for Santa Fé. Thus, would the youth seek his fortune.

Carson reached Santa Fé in the month of November 1826, and went thence to Fernandez de Taos, eighty miles northeast of Santa Fé, and spent the winter with an old mountaineer named Kincaid, or Kin Cade, who taught him something of the lore of the mountains. Perhaps a little homesick, in the spring of 1827 he started back for the East, without a penny in his buckskin pockets. He worked back homeward on the long journey down the Arkansas to a point about four hundred and fifty miles east of Santa Fé, and there, at the ford of the Arkansas, met another band of traders, westbound, to whom he hired out as a teamster.

He again reached Santa Fé, still without a dollar, and went as teamster thence as far south as El Paso, returned to Santa Fé, and again to Taos. He was learning Spanish and learning New Mexico all this time. He now hired out as cook to Ewing Young, and continued in this interesting capacity until the spring of 1828. Again, he started East, again failed to win farther than before, and joined another westbound party, to reach Santa Fé a third time. Now he could do a bit in Spanish, and hence engaged as interpreter for Colonel Tramell, and wagoned it as far south as Chihuahua, in old Mexico. All this sounds full easy, yet even these few journeyings hitherto covered many, many weary, blistering miles.

In far-off Chihuahua young Carson hired out as a teamster, serving in the employ of Robert McKnight. He went to the Copper Mines, on the Gila River, and thence back once more to Taos, which latter place was to serve as his headquarters all his life. All this time, it was Carson’s ambition to be something better than a cook, or a teamster, or even an interpreter. The adventurer’s blood was in his veins. It was April of 1829 when he joined Young’s party of trappers, and soon thereafter he saw his first fight, in which the white men killed some fifteen Indians.

This band now worked toward the West, trapped down the Salt River, and reached the head of the San Francisco River. They concluded to go over to the Sacramento River of California, then reported to abound in fur. On the seventh day’s journey to the west and southwest, they reached the Grand Cañon of the Colorado. These trappers always remembered the Grand Cañon of the Colorado; for it was near there that they bought a horse of some wandering Indians, and ate it. They were very hungry.

There were no trails across the interior desert in those days. Hence, although these were not the first adventurers to cross to California, they were in effect pioneers. In some way they succeeded in reaching San Gabriel Mission of California, and thence—by some very wonderful geography on the part of one or two biographers—they reached the Sacramento River. In the San Joaquin valley, they met Peter Ogden’s party of Hudson Bay trappers. So, we may see that the West was far from being an unexploited country when Kit Carson began his travels.

This early transcontinental party was successful in its trapping, and the leader, Ewing Young, visited San Rafael with the catch of furs and sold it out in entirety to the captain of a trading schooner. He then bought horses for the return East. The Indians of the Sierra foothills promptly stole many of these horses. This was his first independent scouting trip. He and his party killed eight Indians and retook the horses. Already his hand was acquiring cunning in the stern trade of Western life.

September of 1829 found Kit Carson back again in New Mexico. It took the party nine days to ride from Los Angeles to the Colorado River. Thence they seem to have descended the Colorado to tidewater, to have crossed over to the Gila, and to have ascended the Gila to San Pedro. There was some more horse stealing, a little exchange on both sides between the whites and Indians in this line. The whites needed horses, for they had no other meat. Yet in some fashion they won up the Gila River to the copper mines of New Mexico, which, we may see, was ground already known to Carson. Here they cached their furs, since these would be contraband under the Spanish law, nearly all these wanderings having taken place in the Spanish territory that was the western goal of the early commerce of the prairies.

In time, the party turned up at Santa Fé, reaching that city in April 1830, where the leader, Young, disposed of his furs, the net result for eighteen men during a term of one year being twenty-four thousand dollars. Kit Carson was now twenty-one years of age, and he was fully initiated in his calling. We cannot appreciate these journeyings except by taking an accurate map of the great Western country, and following, finger by finger, along stream and across mountain, the course of the early voyagers.

This, however, is but the beginning. In the fall of 1830 the noted Western fur trader, Fitzpatrick, organized a strong party, and it was matter of course that Carson would find his way into it. This band visited the Platte River, whose long southern arm reaches deep down into the heart of the Rockies. Thence, along good beaver waters, they moved over to the Green River, Pacific waters, also historic in the fur trade. We find them later in Jackson’s Hole, east of the range. Then they moved west to the Salmon River, and joined others of their party, who had started out slightly in advance of them, and “for whom they had been looking,” as one chronicler naïvely advises us. It was a search and a meeting in the heart of a wilderness many hundreds of miles in extent.

The winter of 1830-1831 was spent by Carson on the Salmon River. Now enter those stern warriors of the North, the Blackfeet. Kit saw four of his companions killed. He was inured to such scenes, and the incident gave him no pause. April of 1831 found him on the Bear River. Moving, always moving, we see him now on the Green River, again in the “New Park” of Colorado, on the plains of Laramie, again on the long South Fork of the Platte, and presently on the Arkansas. Beseech you, let your finger ever follow on the map; and accept warrant that if your following has been honest, your eyes shall stare in wonder at these journeyings.

This winter camp on the Arkansas River furnished a certain amount of interest. A party of fifty Crow Indians raided the camp and stole a number of horses. It was Carson, once more, who was elected to lead the pursuit. Twelve Indians were killed by the young leader and his hardy riflemen. Carson was now accepted as one of the captains of the trails. He had fully learned his bold and difficult trade.

In the spring of 1832 Carson’s party moved to the Laramie River; moved again to the headwaters of the South Fork of the Platte, and caught beaver and fought Indians for a few months; from the Laramie to the Bayou Salade, or Ballo Salade, as it was sometimes spelled in those days.

Carson returned to Taos in the fall of 1832, well laden with furs. At Taos, Carson met Captain Lee of the United States Army, a partner of Bent who founded Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas. Captain Lee had a cargo of goods that he wished to take to the rendezvous of the trapping bands for that year. Kit joined him, and in October of 1832 they pushed on, traveling part of the time on the old Spanish Trail to California. They reached the White River, the Green River, the “Windy” River, and here, as though by special plan, they met their band of trappers, erected their skin lodges, and passed the winter. Kit joined the Fitzpatrick party in the next spring, but after his own restless fashion broke away, with only three companions.

In the summer of 1833, Kit had his historic adventure with two bears, which chased him up a tree, and which he repelled by beating them over the noses with a branch broken from the tree. All this time, Carson is fitting himself for his work in the West as guide for “explorers.” We find him with fifty men, pushing up to the headwaters of the Missouri River, and later he and some companions turn up along the historic Yellowstone River, a country then well known in the organized fur trade of St. Louis.

We do not discover that he ever went into the regular employ of any of the fur traders. No engagé or ordinary “pork eater” he, but a companion nearly always of these independent fur traders, the individual gentry of the wilderness. We find him now becoming acquainted with the Big Horn. He knows also the three forks of the Missouri; and he visits the “Big Snake” River and the Humboldt River, then called Mary’s River, since scientists still were scarce in the Rockies.

He wanders continually back and forth across the upper Rockies. Brown’s Hole, Jackson’s Hole, Henry Lake, the Black Hills, all the upper waters of the great rivers, the Columbia, the Snake, the Green, the Colorado, the Platte, the Missouri, the Yellowstone, the Arkansas,—you shall hardly name any well-known Western region, any remote mountain park, any accurately mapped Western stream which you shall not, providing you have faithfully followed the wanderings of Kit Carson, discover to have been familiar to this man even before geographies were dreamed of west of the Missouri River.

It would be but wearying to go on with the monotonous chronicle of repeated journeys back and forth, of hardships, of toils and dangers, of the round of the trapper’s employment, of the wildlife at those wild, strange annual markets of the mountains, the trappers’ rendezvous. It will suffice us and serve us to remember that Carson practically closed his life as a trapper in 1834, this date marking the end of eight years steadily employed by him in trapping and trading and in learning the West. In 1834 he and such companions as Bill Williams, William New, Mitchell, Frederick, and scores of others of his old-time friends, found themselves practically without a calling. When, after one long expedition west of the range, they readied Fort Roubidoux, it was only to discover that furs had gone low in price.

The advent of the silk hat had caused terror in St. Louis, and gloom throughout the Rockies. The day of the beaver trade was at an end. That animal, of so monstrous an importance in the history of the American continent, was now to assume a place far lower in estimation. Our bold, befringed mountaineers learned that it would no longer pay to pursue it into the remote fastnesses of the Rocky Mountains. Yet the beaver had served its purpose. Following its tooth-marks on the trees, there had pressed on to the head of every Western river a man qualifying for office as guide of the west-bound civilization beyond the Missouri. Kit Carson, type of the graduated trapper and adventurer, had had his schooling.

Yet a man must live, and if there be no price for beaver peltry, he must turn his hand to something else for occupation. For eight years Kit Carson served as hunter for the post, well-known as Bent’s Fort, on the Arkansas River. There he fed forty men on the wild meat of the plains, and during his eight years of hunting killed thousands of buffalo, elk, and deer. He saw the plains in all their ancient, undimmed splendor, and whether he most loved the mountains or the plains he himself never could tell. Carson at an earlier time had married an Indian girl, and during his engagement at Fort Bent he sent his one child, a daughter, to St. Louis for the purpose of acquiring an education. There the daughter married, went to California, and apparently passes from the scene. Carson’s later marriage was with a Mexican woman much younger than himself.

If in the year 1834 Carson terminated the first term of his Wanderschaft, in 1842, when he closed his first engagement as hunter for Bent’s Fort, he completed the second season of his Western life and was ready for the third. In that year he joined a wagon train bound eastward, having determined to revisit his old home in Missouri, which he had not seen for sixteen years. The visit was sad and cheerless enough. He returned to find his parents dead and forgotten, the old homestead in ruins, and not a friend left.

He hastened thence to St. Louis, but ten days of even the capital of the fur trade proved sufficient for him. Soon afterward, as is stated by his most reliable biographer, he by mere chance met young Frémont, then bound West to “explore” the Rocky Mountains, more especially that part of the Rockies in the vicinity of the South Pass. Frémont’s guide did not materialize at the time, and Carson’s modestly proffered services were engaged by the army officer, who needed a guide across country, which to many a Western man was as familiar as his own dooryard.

During his first expedition, Carson does not seem to have been much valued by Frémont. Basil Lajeunesse was the favorite, and it was always Basil Lajeunesse here, there, and everywhere; Carson, a man of much greater experience and reliability, having not, as yet, come into his own as a guide, though forsooth there was small need of guiding on this journey. Frémont engaged Carson at one hundred dollars a month, and he was the twenty-eighth man in the party, which also included two boys, young relatives.

Little of the eventful occurred in the long journey across Kansas to Fort Laramie, and so at last they arrived at the South Pass, having met no Indians at all, although they had feared the Sioux. Frémont rode across the gentle summit so long known to the fur traders, climbed the mountain that was later named for him, and returned to Fort Laramie in September 1842. Thus ended his first expedition, which began his reputation as a “pathfinder.”

After the first Frémont expedition, Carson returned to Bent’s Fort, and in February of 1843 married the young Mexican woman who remained his faithful companion throughout his life. Carson was sent with a message to Governor Armijo with a warning for the latter, but one hundred of the Mexicans connected with Armijo’s wagon train were killed by the Texans on the historic wagon road up the Arkansas River.

Up to this time Kit Carson had been more savage than civilized. He had never cast a vote for any office. He had lived on the product of his rifle. He had learned the habits of the wild men and wild animals of the West. Yet he seems to have gained something of that forcefulness and self-confidence which sooner or later is bound to impress itself upon others; for on May 29, 1843 we find Frémont again sending for him, and asking his services as guide for his second expedition.

This time it was Frémont’s purpose to connect his last year’s work with the Pacific Coast surveys, which had been begun by Wilkes. All know how Frémont exceeded his orders, how his wife pluckily held back from him the knowledge of his recall, and how this transcontinental expedition, by no means the first, though one of the most widely acclaimed, made its way over grounds new to Frémont but old to Carson. The first part of the journey was among the old trapping grounds along the North Fork of the Platte and on the Sweetwater, thence to Salt Lake—all points fully known to the fur trade many years before. The journey thence ran to Fort Hall and along the perfectly determined trail northwest to the Columbia River. Frémont then pushed on to Tlamath Lake, Oregon, heading thence for California.

This country between the Tlamath Lake and the Sacramento valley was new even to Carson. Everybody supposed that there was a great river, known as the Buena Ventura, which rose on the west side of the Rocky Mountains at a point directly opposite the headwaters of the Arkansas, and flowed westward directly into the Pacific Ocean. The little fact of the Sierra Nevada Mountain range was wholly overlooked.

Carson honestly did his best, but he was in the hands of a leader who undertook to cross the Sierras with a packtrain where there was six feet of snow, and with a party the total number of which counted only two men who had ever before worn snowshoes in all their lives!

After many hardships, the expedition worked to the south and southeast of the Tlamath country, and got down near to what is now known as Pyramid Lake. Then they started across for the Sacramento, not having discovered the fabled Buena Ventura. Carson, quiet, not boasting, openly confessing his ignorance of a country he had never seen, none the less in these hard conditions proved serviceable as a guide. He pushed on ahead, and from a peak of the Sierras got a glimpse of the Coast Range. He had not seen this Coast Range chain for seventeen years, but now he noted two little mountains that seemed familiar to him. He told his leader that if only they could win across the Sierras, they would presently be in a country of warmth and plenty.

The men by that time were eating their saddle leathers, the mules were eating each other’s tails. It was a starving, freezing time, this foolish bit of mountain work, such as in all his trapping experience Carson never saw equaled. Yet, at last, they did reach Sutter’s Fort, on March 6, 1844, two thousand miles from Fort Hall. Some of the men were physically ruined and mentally deranged from their sufferings. It was military and not mountain leadership that was responsible for all this.

But our continually traveling man, this little man, Kit Carson, was not to have any rest even in the pleasant valley of the Sacramento. We find the expedition soon starting East again, now by way of the San José valley, over the Sierras to the Mojave River, country long known to the traveling trappers. Here Carson and his friend Godey conducted a little enterprise of their own, undertaken in sheer knight-errantry, on behalf of a party of Mexicans who had been nearly annihilated by the Indians. These two men rode a hundred miles in thirty hours, and alone attacked a large camp of Indians, killing two of them and stampeding the remainder.

The Frémont party arrived at Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas July 2, 1844. They had traveled somewhere between thirty-five hundred and four thousand miles, had circumnavigated the mysterious “Great Desert,” and for eight months had never been out of sight of ice and snow. Frémont was able to report upon the great Columbia River, and he and his contemporaries did not hesitate to extol the value of Oregon as a gateway of the Asiatic trade—a line of commerce which for half a century did little to establish the truth of their prophecy.

This, then, was the end of the first exploration of the Rockies accompanied by thermometer and barometer rather than by trap sack and “possible bag.” It was of value. If we were asked, what was the most valuable result of this second expedition of Frémont? We should be obliged to answer that it was his mention of the great value of the Western grasses. Frémont was an observer, a chronicler, a writer. It was he who first began to bring back accurate story of the resources of the West.

The mineral wealth of the West, over which the trappers had tramped for a quarter of a century, was, as yet, unsought and unsuspected by Frémont or anyone else. It was to be first the fur trade, then the mining trade, then the cattle trade in the trans-Mississippi West; and after that the agricultural life, followed by the days of swift transportation, of change, of transition and expansion and gourd-like growth in all visible ways.

We are now well forward in the third era of Kit Carson’s career. If, at first, he was a trapper and hunter in order that he might become a fit guide, during the third stage of his life he was to be accepted as the authorized guide of the most important preliminaries for the westbound movement of the trans-Mississippi population. After the close of the second Frémont expedition, and during the year 1845, Carson tried to be a ranchman or farmer, pitching his tents for the time about fifty miles east of Taos. It was of no avail. Frémont called for him once more. The farm was sold for half its value, and once more Carson set his face toward the West, in company with a Frémont now older, better seasoned and of better judgment. A more direct trail across the Great Basin and into California was desired than that taken either in going or returning on the second expedition.

Carson was the one to go ahead. He traveled alone for sixty miles west of the Great Salt Lake, directly into the desert, and the rest of the party came up to his signal smoke. Thence they pushed on to the Carson River, searching still for a new pass over the Sierras into the valley of the San Joaquin. At last, they won across, as did the earlier trappers, and again they reached Sutter’s Fort in due time. A branch of the main party, that headed by Talbott, did not appear at the appointed meeting place. It was Carson, of course, Carson the traveler, who was dispatched down the San Joaquin valley to discover the truth of a rumor that Talbott and his party had appeared in that locality. Needless to say, the wanderers were found.

Now there broke out the Mexican imbroglio, in which the part of Frémont is well known. For a time, Frémont’s party moved north, along the Sacramento, thence toward the Columbia River. They did not know that war had been declared between the United States and Mexico. Lieutenant Gillespie, hot on their trail, brought the message that hostilities had broken out.

In Oregon, in the Tlamath country, came the night attack in which Basil Lajeunesse and three others of the party were killed. Carson saw his companion, a brave Delaware Indian, stand up and receive a half-dozen arrows from unseen foes. He joined the pursuit in the dark, and later, on the backward trail to California with Gillespie, helped execute the stern mountain vengeance on the Tlamaths, leading the mountaineers in all their desperate little fights.

The exploring party had now become military, and so the flag, led and backed by American mountaineers, went up above a Western empire. As to the services of this far-traveling mountain man to his leader and to his country, we can scarcely overestimate them. Some idea of the confidence in which he was now held may be gathered from the fact that, after the Frémont operations in California, Carson was sent with dispatches to Washington, in order that the government might know what was happening on the far away Pacific slope.

He started on September 15, 1846, and it was asked of him that he make the entire trip to Washington inside of sixty days; this at a time when there was not a foot of railway west of the Missouri, and when all the country from the Pacific to the Missouri was, more or less, occupied with hostile Indians. None the less Carson started, the first overland rider to bear dispatches on a continuous journey of this nature.

By October sixth he was far toward the eastward, across the Rockies, when he met General Kearney’s column. Kearney ordered Carson to turn back and guide him westward to California. Without a murmur the little blue-eyed man remarked: “As the General pleases.” He did not stop to visit his own family at Taos, but went back once more to lead the westbound flag. By December 3rd, the slow column had reached California, and here it met more warlike experiences than it liked or had believed possible. The California Mexicans who fell upon Kearney’s column were fighters. They killed fifty of the Americans, surrounded the remainder, and bade fair to exterminate the entire expedition.

Witness again the service of the scout and guide. Carson and Lieutenant Beale of the Navy were sent out as special messengers to San Diego. They got through the beleaguering lines, and after a perilous journey arrived at San Diego and secured the desired help. This sort of thing was nothing new to Carson. It was so severe for Beale that he went deranged, and it took him two years to recover from his journey, brave man and bold as he was. The Army and Navy had not the seasoning of the American mountain men, the hardiest breed ever grown on the face of the globe.

At Los Angeles, Carson finally rejoined Frémont, in time for that tempest in a teapot wherein Frémont and Kearney fell at swords’ points. These things are of no moment, yet it is significant that in March 1847, Carson was sent once more as dispatch bearer to Washington. He went light and speedy as before, met the Indians on the Gila, fought them, and won through. This time he reached Washington, after his long and steady ride across New Mexico and down the Arkansas River to the Missouri, arriving in the month of June, after having made four thousand miles in three months.

In Washington, Carson met Jessie Benton Frémont, wife of Frémont and daughter of the arch-protector of the fur traders and of Frémont, Thomas Benton. Carson was now appointed lieutenant of the rifle corps of the United States Army; a commission which, by the way, was never ratified, although he did not know this for some months. He was sent back, four thousand miles, to bear dispatches in return. He crossed the Missouri River, fought the Comanches at the Point of Rocks, got through them, pushed on west as steadily as ever, and reached the Virgin River, in the dry Southwest, before he met his next Indian fight. He and fifteen comrades here stood off three hundred Indians. In due time he reached Monterey, and after this he took service against the Mexicans on the border for a time.

So energetic a man cannot be allowed to rest, and, in the spring of 1848, he is sent back once more to Washington. The physical frame of any other man except Kit Carson had been by all these journeyings too far racked to enable him to make this long and hazardous trip. The souls of most men would have failed them long ere this. Yet this hardy, tough little man, just big enough for steady riding, cheerfully undertakes his third journey across the mountains as dispatch bearer for the United States Army.

This time he meets Utes and Apaches, fights them, wins through them, and goes on. He stops on this trip just for a day to see his family at Taos, averaging a visit home about once in three years. It is here that he learns that he is not a lieutenant, after all; but that does not check his loyalty to the flag. He goes east now up the Bijou, and down the Platte to the Republican Fork, in order to dodge certain Indians, who, he hears, are numerous and bad along the Arkansas.

He reaches Washington safe and sound, of course; starts back for New Mexico; and arrives there in October 1848. Figure yourself, if you like, as chief actor in a quarter of a century of such traveling as was done by Kit Carson. His travels are given thus in detail that we may have just estimate of the man of those days, of the tremendous demands upon his courage and endurance. Only the West could produce such a man.

Now we may picture Kit Carson in the fourth stage of his career, as settler and rancher. He was at home now, but he knew no rest. He fought the Apaches, and guided Colonel Beall against that tribe and the Comanches, in an endeavor to round up all the Mexican prisoners in the hands of the Indians, who were to be returned to their own firesides. After this little expedition Carson was once more a man without an occupation. There was a lull in fighting and scouting. Having no profession except that of trapper and of guide, he cast about him and once more determined to be a ranchman. He and his friend Maxwell established a ranch fifty miles west of Taos, at what is known as Rayado or Rezado. Again, he joined an expedition against the Apaches, a day-and-a-half to the southeast, a disastrous expedition, in which he was not leader, but might better have been. At another time he helped chase some Apache thieves, and assisted in the killing of five of them. Our army could never catch the Apaches, the Nez Percés, the Comanches, the Crows, the Blackfeet. Kit Carson always could and did.

This Indian fighting, however, did not bring money to his coffers; therefore in 1850 we find him and a partner taking a band of horses from New Mexico up to Fort Laramie, a journey of five hundred miles. After this followed some more horse stealing on the part of the Indians, yet more punitive expeditions, and acting as an amateur sheriff, for which service Carson had become a necessity in the district. He was not afraid. He could read the signs of the trails. He could ride.

In 1851 Carson and Maxwell tried their hands at a bit of the Santa Fé trade themselves, although this was long after the glory of the old-time wagon trade had departed. They got a train load of goods at St. Louis, and started westward up the Arkansas, after the old-fashioned way.

And now comes one of the most romantic, indeed one of the most pathetic pages in the whole history of this brave man, if not in all Western history. Rebelling at the tameness of ranching and horse trading and wagon trafficking, longing once more for the freedom of the trapping trail, Kit sent word about among his old friends, the free traders of the Rockies. A party of eighteen old-time long-haired men was made up; and thus they sallied forth, with rifle and ax and pack and jingling trap chains, in the fashion of the past, making once more deep into the heart of the Rockies. They visited the Arkansas, the Green, the Grand, all the loved and lovable parks of the mountains. They came back through the Raton Mountains, bearing with them abundant fur. They said that it was their last trail; that they had seen the old streams they loved, in order that they might “shake hands with them and say goodbye!” This expedition was made for sheer love of the old life, which they knew had now gone by forever. The settlement of the West was at hand.

We might believe that by this time Kit Carson would have had enough traveling, and would have been content to bound his ambitions by the little mountain valleys that lay about him in New Mexico. Not so, however, for we find his next exploit to be the unusual one of a sheep drive to far-off California. He assembled a band of six thousand five hundred sheep, and following by easy stages along the old mountain trails with which he was so familiar, at length arrived with his herd, in August 1853, at his destination. He sold his sheep at the good price of five dollars and a half a head, this being the most considerable and most profitable speculation in which he had ever engaged in his life.

He remained for a time in California and looked about him, but he found California no longer a wilderness occupied by wandering and infrequent trappers, but a land overflowing with gold, and tenanted with a restless and swiftly increasing population. He saw a San Francisco of fifty thousand souls spring up as by magic within sight of those two little hills of the Coast Range that had marked the land of salvation for Frémont and his party in their starving journey across the Sierras. He found himself a hero in this new and busy San Francisco;, but he was ever unfamiliar with the art of being a hero, so presently he left the town and returned again to New Mexico, traveling this time by the old trail to the copper mines, by which he had led Frémont in his first journey east from southern California.

Carson was now living in a West experiencing sudden and general change. The old West was nearly gone, and all its ancient ways. The government at Washington was familiar with the doings of this quiet little man of New Mexico, and it was suggested that he would make a good Indian agent for the district of New Mexico. At this time, the Utes and the Jicarilla Apaches were resistant, and one of Carson’s first acts was to ride two hundred and fifty miles into the Ute country. He led the forces that broke up the coalition between the Utes and the Apaches.

Later in his life, leaving the United States service as Indian agent, Carson was made colonel of a regiment of New Mexican volunteers, during the War of the Rebellion. He was brevetted brigadier-general of volunteers. In the closing years of his life, he was known as “the general” among his friends.

Kit Carson’s death occurred at Fort Lyon, Colorado, May 23, 1869, the immediate cause being an aneurism of the aorta. Eight years before, Carson had sustained a bad fall, and had been dragged for a distance by his horse. From this hurt he never fully recovered. “Were it not for this,” said he, meaning his mishap, “I might live to be one hundred years of age.” Yet, knowing that he was doomed, he lived bravely and sweetly as ever, and to the end remained as unpretentious as during his early days.

“It was wonderful,” says the chronicler who saw his last hours and who heard most of the biography of Kit Carson read in the presence of the man himself, “it was wonderful to read of the thrilling deeds and narrow escapes of this man, and then look at the quiet, modest, retiring but dignified little man who had done so much. He was one of nature’s noblemen, a true man in all that constitutes manhood, pure, honorable, truthful, and sincere, of noble impulses; a knight-errant, ever ready to defend the weak against the strong without reward other than his own conscience. His was a great contempt for noisy braggarts of every sort.”

So, surrounded by his friends, facing the impending end with his customary bravery, Kit Carson passed away. There was a struggle and a fatal hemorrhage. “Doctor—compadre—adios!” he cried. “This is the last of the general,” said his friend. So passed one of the last of the great Westerners.