The Way to the West: Davy Crockett (Historical Reprint)

Historical article reprinted from the book "The Way to the West and the Lives of Three Early Americans: Boone, Crockett, Carson" written by Emerson Hough in 1903.

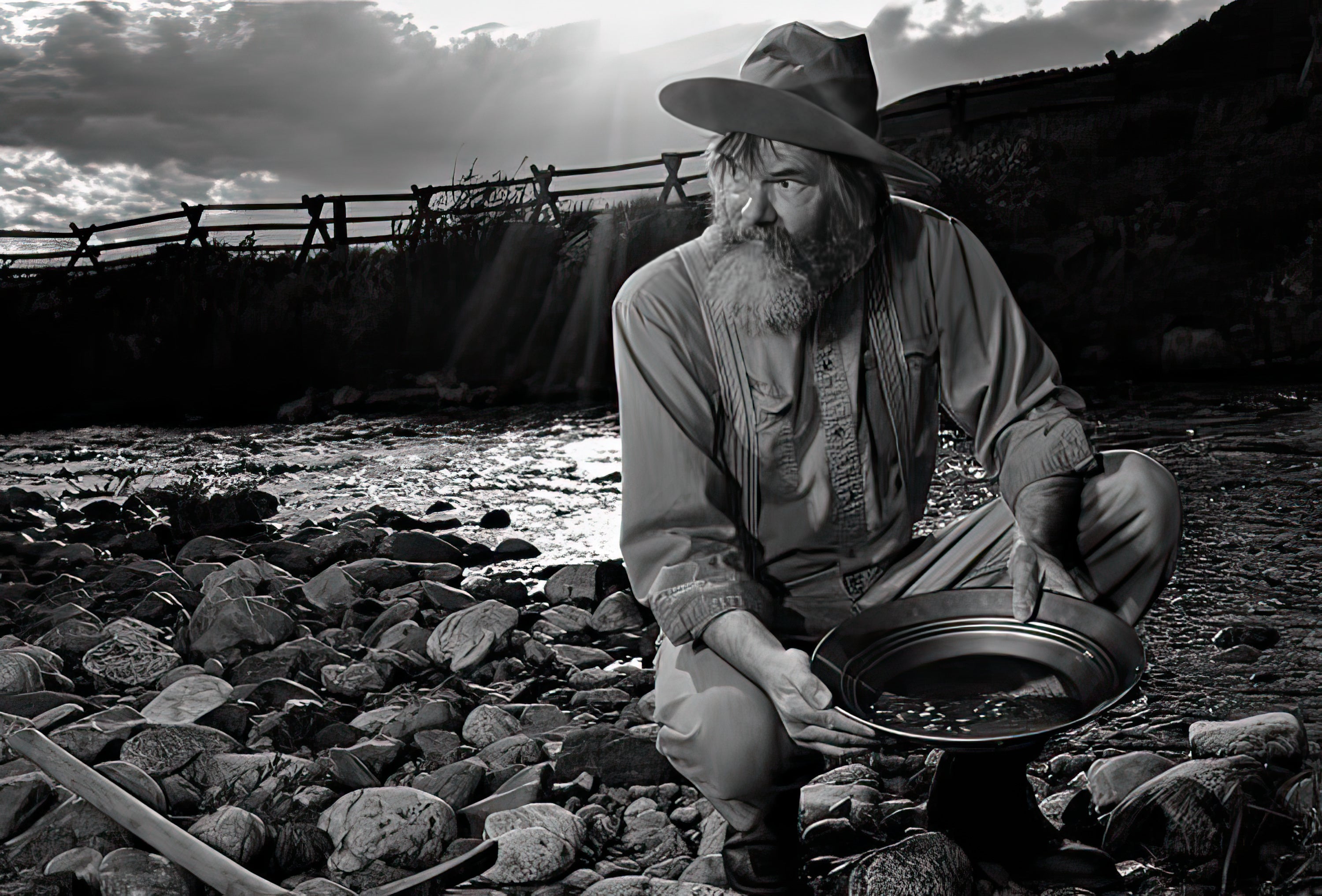

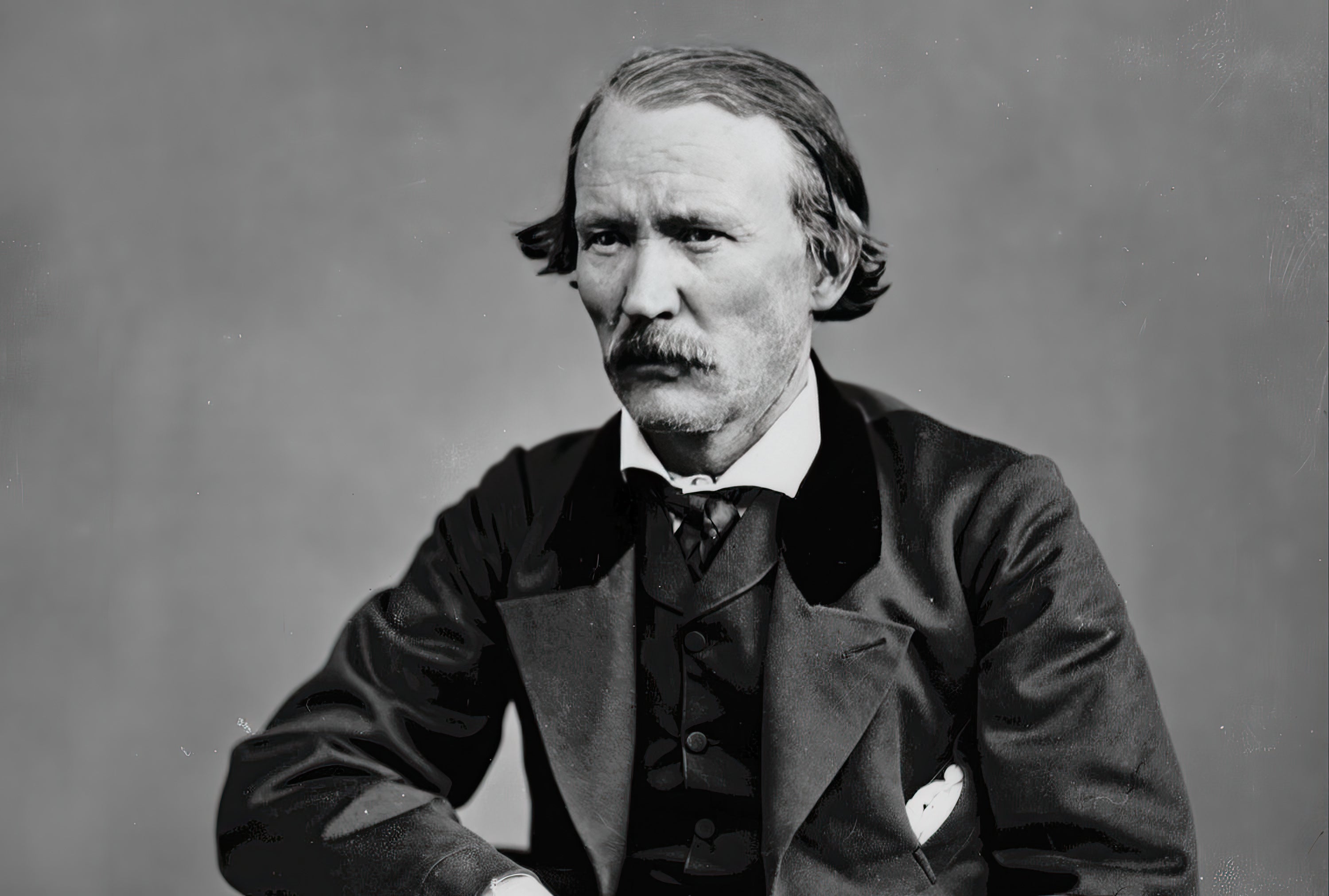

Related Art: Davy Crockett

There is no figure of speech that so exactly describes the westward advance of the American population as that which compares it to the feeding of a vast flock of wild pigeons. These, when they fall on a forest rich with their chosen food, advance rapidly, rank after rank. As those in the front pause for a moment to feed, others behind rise and fly on beyond them, settling for a time to resume their own feeding operations. Thus, the progress of the hosts resembles a series of rolling waves, one passing ever on beyond the other, each wave changing its own relative position rapidly, yet ever going forward.

It was so with the American people. The Alleghanies could not stop them in their westbound march, nor the terrors of a relentless Indian warfare, which endangered lives dearer to the rugged frontiersman than his own. Nothing would do until the pathway of the waters had brought the American settler to the Mississippi River, the great highway that, whether by whim, chance, or design, had now become wholly the property of the growing American government. Having arrived at the Mississippi River, the population could not rest. Those behind pressed ever on.

Once across the Alleghanies the pathways had been pointed out by nature; beyond the Mississippi these pathways were reversed. Man had not wings like the wild bird. His pilgrimage must still be slow, his methods of locomotion clumsy. The paths no longer lay even with the currents of the streams. The adventurer into the West must, for the most part, follow the reversed pathways of the waters. Briefly, the journey of the frontiersman from Pennsylvania to the Mississippi was one of angles, the first leg running to the southwest, thence northwest, thence southwest. The pilgrimage profile from the Mississippi to the Rockies was equally angular. The line of travel did not, for the most part, run directly to the west. It angled out and upward, wherever water transportation led, and where the streams showed the way.

In the story of Daniel Boone, we see how he moved again and again, seeking ever to edge a little farther to the west than his nearest neighbors. The great frontiersman, Davy Crockett, beloved of the American people, gives us instance of this patient progress of the westbound, halting, advancing, but never tiring.

Davy Crockett, backwoodsman and bear hunter, magistrate, legislator and congressman - a man who, at the time of his marriage, scarcely knew one letter of the alphabet from the other, yet at middle age was one of the best-known figures of the American political world, and who was even mentioned as a possibility for the presidency of the United States, a man who lived like a savage and died like a hero—one of the most uncouth gentlemen who ever breathed—such a man as this could have been the product of none but an extraordinary day.

In some fashion, the names of Boone and Crockett are often loosely connected. They were in part contemporaneous though not coincident. Showing in common the rugged traits of the typical man of their time, they were yet distinctly unlike in many qualities. A writer who knew both men states that he considered Crockett the mental superior of Boone. After weighing carefully all the evidence obtainable—and there is much more information available concerning Crockett than in regard to Boone—one would be disposed to differ from such an opinion.

Boone was the simpler and sincerer soul, the graver and more dignified figure, Crockett the more magnetic personality, the more plausible, if at times less candid, man. One man was practically as ignorant as the other. Boone had no taste for political life, and his sole wish was to live ever a little beyond that civilization of which he was the pioneer and guide.

Crockett, built also of good, common, human clay, for two-thirds of his life seemed animated by no greater ambition. Then all at once we see him turned politician. He succeeds, and his name grows larger than his neighborhood and country. Not knowing the basis of the tariff, ignorant of the text of the Constitution, master of the practice, but unable to explain the theory, of a caucus or a town meeting, he finds himself owner of a seat in the United States Congress, fairly the central figure of that Congress, the cynosure not only of the South but of the East and North.

He is, at this time, nothing but a great, good-humored boy, the very type alike of an open-handed generosity, and an open-mouthed and sometimes ill-timed levity. He is the product of political accident. Yet, wonder of wonders, we find this man, quite past the time usually assigned as the limit for the development and fixing of a man’s character, suddenly blossoming out into a second development, a second manhood, more thoughtful and more dignified than that of his early days. Without education when he started for the halls of Congress, he gains that education more rapidly than did ever man before.

Crockett returned to his home a graver and broader man. Even his speech had gained freedom, ease, and clarity, though still he delighted, perhaps more in jest than otherwise, to bring in the crudities of expression, the quips and quirks of that language through which he had, to his own surprise and without his own plan, won his sudden notoriety—a notoriety that was later to turn to fame.

There is not to be found in all the history of American statesmanship so swift and sound a ripening into mature thought as that of this backwoodsman, the first political “mugwump” or independent; who engaged in politics for reasons of self-interest, and then all at once grew big enough to set self-interest aside and to do what seemed to him wise and right - a type of statesmanship now well-nigh defunct in America. And yet we see him, in the pang of his first decisive political defeat, growing bitter at his reverses, losing the genial philosophy of his earlier years, even renouncing his country, and forthwith turning away from family, friends, and commonwealth to seek a new fortune in an alien land.

Some biographers of Crockett accord to him in this act the motives of bold knight-errantry, yet impartial review of known facts leads one to believe that Crockett’s abandonment of his family and his somewhat erratic journey into Texas were most easily explicable by reasons of a plausible self-interest. He was seeking political advancement along lines of less resistance. Then, finding himself a member of a party of souls as adventurous as himself, souls reckless and unrestrained, ardent, eager, fearless, yet without a leader and without a definite plan, Crockett the backwoodsman, Crockett the thinker, the orator, the statesman, if you please, flings himself with the others into fatal fight, rages with them in the most glorious struggle yet chronicled in the pages of American history, fights like a Titan, dies like a gallant gentleman, helps write the shining history of that squalid hut in old San Antonio, and makes possible one of the most burning sentences that ever adorned monument above hero’s grave: “Thermopylae had three messengers of defeat; the Alamo had not one!”

Here are contradictions that might be thought sufficient to give us pause; yet not contradictions large or conclusive enough to rob Davy Crockett of aught of the fame that has been accorded him by the American people. In order to reconcile or explain these contrarieties, and hence to understand this searly American, we shall do well to review the better known and most authentic incidents of his peculiar career.

Crockett does not go so far back in the history of the westbound American as does Daniel Boone. The latter died at the age of eighty-six. Crockett, who died about ten years later than Boone, was but fifty years of age. His life falls in the trans-Mississippi period of the Western population movement. He was born August 17, 1786, in Greene County, Tennessee. His grandfather was an Irishman who came to Pennsylvania, then moved west in order to avail himself of the settlers’ right of four hundred acres of land, which carried the preemption right of an additional one thousand acres. A goodly portion of a goodly earth lay ready to every man’s hand in that day of American opportunity.

The second Crockett homestead, on the Holston River, was broken up by the Indians, who killed the parents and several of the children, John Crockett, David’s father, being one of the few who escaped. John Crockett became a Revolutionary soldier, and after the Revolutionary War moved to North Carolina, just as did the father of Daniel Boone.

Following the path of the earlier Argonaut, Boone, John Crockett in 1783 crossed the Alleghanies, but settled in eastern Tennessee, instead of Kentucky. In this wilderness David was born. It was a land without religion, without schools, without civilization. In such an environment the weaker children died. Naked as a little Indian, David Crockett ran about the rude cabin, and lived because he was fit to survive. One of his earliest recollections is that of an incident in which his uncle, Joseph Hawkins, figured. Hawkins accidentally shot one of the neighbors, the ball passing through his body. There was no surgical skill possible, and it was considered the proper thing in the treatment of this wound to pass a silk handkerchief, carried on the end of a ramrod, from one end to the other of the wound. Crockett appears to have seen his father pull a silk handkerchief entirely through the body of this wounded neighbor. It was a strong breed, that of Tennessee a hundred years ago!

Of course, this settler must move west, and again west. At the fourth move of his life he located on Cove Creek, the boy Davy being now about eight years of age. About this time, Crockett’s father lost his gristmill by fire. Naturally, the remedy for this was to move, and he again took up his journey, settling this time on the road between Abingdon and Knowlton, where he opened a rude tavern, patronized mostly by teamsters of the roughest sort - certainly a hard enough environment for the coming statesman.

The earliest description of Crockett represents him to be “a wiry little fellow, athletic, with nerves of steel.” Even in childhood he was given to fierce encounters, yet he was of an open and generous disposition. He grew up practically without care, his father, if truth be told, being a man of somewhat gross and drunken habits. Davy finally, at the mature age of thirteen, forsook the paternal roof and set out in the world for himself.

He chanced fortune with drovers, driving cattle to the eastward, and learned to be hostler and general utility man, becoming acquainted with the trail that ran between Abingdon, Witheville, and Charlottesville, Orange Court House, and other points in Virginia. He worked for a few months as a farm hand in Virginia. He wandered into Baltimore, with wonder noticed the shipping there, and came near becoming a sailor, but was rescued from that fate. Buffeted by fortune from pillar to post, he worked one month for a farmer at a wage of five dollars. He went apprentice to a hatter and worked for eighteen months for nothing, at the end of which time the hatter unfortunately failed in business.

Poor Davy spent two years in these wanderings, and was fifteen years old when all at once he again dawned upon the paternal grounds in eastern Tennessee. These two years had been spent in considerable physical discomfort and anguish of spirit, and the journey home was accomplished only after many dangers and difficulties. Crockett admits that at this time he did not know the letters of the alphabet. His father, shiftless as ever, had been lavish with his promissory notes. He offered Davy his “freedom” if he would work six months for a neighbor to whom he had given a note for forty dollars. Davy generously did so, and capped it off by working another six months and taking up another one of his father’s notes, for thirty-six dollars. This last he was not obliged to do, yet in spite of these bitter surroundings, there had flowered in the young savage’s heart a certain feeling of family honor.

Now the boy backwoodsman became conscious of his own infirmities. He went to school six months, the only schooling he had in his life. He learned to write his name, to spell to some extent, to perform a few simple sums in arithmetic. Twice blighted in love at eighteen years of age, he married a pretty little Irish girl, a daughter of a neighboring family. “I know’d I would get her,” says he, “if no one else did before next Thursday.”

Crockett was married in his moccasins, leggings, and hunting shirt. His bride was dressed in linsey-woolsey. There was no jewelry. The table on which the wedding feast was spread was made of a single slab. The platters were of wood, the spoons of pewter and of horn. In his own abode, as he first entered it, there was no bed and not a chair, a knife, or a fork. Yet, after the expenditure of fifteen dollars, which he borrowed, Crockett and his wife “fixed the place up pretty grand,” and found it good enough for them for some years. Here two boys were born to them.

At the ripe age of twenty years, that is to say, in the year 1806, Crockett considered it necessary for the betterment of his fortunes that he should remove farther toward the West, this having been the universal practice of his kind. He journeyed for four hundred miles through the Western wilderness, taking his family and household goods with him. Their transportation, as we are advised, consisted of one old horse and two colts. These animals were packed with the household goods. In the wild journey down the Holston, the family, children and all, camped out, enduring the weather as best they might. At last, they came to a halt on Mulberry Creek, in Lincoln County, in what they took to be the Promised Land. The soil was generously rich, game and fish were abundant, the climate was all that could be asked. Crockett built a cabin, and here he lived for two years, much as he had lived in eastern Tennessee. Then, in the easy fashion of the time, he moved once more, this time settling in Franklin County, on Bear Creek, still in the wilderness.

Here we find him living in 1813, at which time the call went out for volunteers to serve in the Creek War under General Jackson. Without much ado, Crockett said goodbye to his family, joining those wild irregular troops who, amid countless hardships, plodded up and down the region of Alabama and Georgia, meeting the southern Indians, destroying them wholesale or piecemeal as the case might be. Crockett marched, counter-marched, acted as spy and hunter, doing his full share of the work.

All the time he was rising in the esteem of his fellow men. He was now a tall, large-boned, muscular man. His hair, we are told, was sandy, his eyes blue, his nose straight, his mouth wide and merry. Never having known anything but hardship all his life, he has, none the less, never known anything but cheerfulness and content. The apt jest and catching story are always ready on his lips. He is the life of the campfire. Gradually, he forges to the front. The qualities of leadership begin to appear.

In all these rude military experiences, although Crockett does not fancy the revolting scenes which in some instances he witnesses at the Indian killings, he shows the ardent nature, the fighting soul. Hence, he respects the fighting man and pays his obedience to General Jackson. There is no hint of that fatal falling out between the two men that later is so suddenly to terminate Crockett’s ambitions.

In 1822, after his return from this war, Crockett’s fortunes once more needed mending, and the remedy, of course, was to move again. He had previously explored nearly all of Alabama, and later investigated southern Tennessee, finally locating on Shoal Creek, in Giles County. Crockett’s faithful wife, the little Irish woman, had died, and he, ever ready to console himself, now married a widow of the neighborhood, an estimable woman, who added two children to his already growing family. This second wife appears to have been a dignified and able woman. Little is known of her, and she seems to have lived the life of the average frontier woman, patiently and uncomplainingly following her husband in all his enterprises and his wanderings. Two packhorses still served to transport all the family goods on this latest journey.

The greed for land had rapidly sent a turbulent population into the Cherokee country of the “New Purchase” where Crockett now resided, and among these lawless souls restrictions were needed, although the country knew no law and had no courts. Crockett was elected judge, without any commission and without any formal process of law. He served wisely, and although unable to write a warrant, he sometimes issued verbal warrants. He claimed that his decisions were always just and that they “stuck like wax.”

Meantime, he had been elected colonel of militia over a bumptious rival. Now, his name came up for the legislature. Crockett inaugurated a canvass on lines of his own. In brief, he talked little of politics, for he knew nothing of such matters. He told a brief story, traded a raccoon skin for a bottle of liquor, treated the crowd, promised to sell a wolf scalp and treat them again, and so passed on to the next gathering. He was elected without difficulty.

But, of course, misfortune once more must overtake our hero, and he must move again, this time as far as he can go and not cross the Mississippi River. This next home, and the last one he established, was made in the northwestern corner of Tennessee, on the Obion River, near the Mississippi River, not far from what is now known as Reel Foot Lake, and in the heart of that wild country then known as the “Shakes.”

This was near the submerged lands affected by the New Madrid earthquakes, a country naturally rich in many ways. It was a canebrake country, a heavily timbered but somewhat broken region, crossed now and again by terrific windfalls locally known as “hurricanes.” You may see such country in the Mississippi Delta today, two hundred miles south of Crockett’s home. Crockett’s neighbors on the Obion were three in number, respectively seven, fifteen and twenty miles distant.

On his trip of exploration, he planted his first crop of corn by means of a sharp stick, just as he had broken the earth at each of his earlier homes. He was rejoiced to find that the corn grew excellently, and yet more rejoiced to know that he had found a superb hunting ground. In his early life his game consisted chiefly of deer and turkey. Here, bear, deer and turkey were numerous, and there were also elk occasionally. The buffalo is never mentioned in Crockett’s life, and that animal had probably by this time, 1822, become practically extinct in Kentucky and Missouri.

Mr. J. S. C. Abbott, in his biography of Crockett, writes of his station at this time: “Most men, most women, gazing upon a scene so wild, lonely, and cheerless, would say, ‘Let me sink into the grave rather than be doomed to such a home as this.’” Such is the point of view of the narrow observer who never knew his America. Not so Davy Crockett. He did not find this region lonely or cheerless. On the contrary, we find him fraternizing with the rude boatmen from points lower down on the Mississippi River, and making himself comfortable. Presently, he goes back after his family, bringing them on to his new home in October of that year. They and their belongings are transported by two horses, this limited cavalcade being still sufficient to carry all the worldly belongings of David Crockett, hunter, warrior, magistrate, and legislator. Davy is still poor, but he does not wish to “sink into the grave.” On the contrary, as he journeys along the wild woodland path he sings, jests and whistles, happy as the birds about him, content among the sweet mysteries of the untracked forests. He is the product of wild nature, as savage as the most savage, a man primeval, unfettered, free. He is the new man, the man of the west, the new-American.

As an example of Crockett’s early electioneering methods, we may cite his procedure in his first canvass for the legislature.

He says: “I didn’t know what the government was. I didn’t know but General Jackson was the government;” a statement not wholly the product of sarcasm. He met Colonel Polk, later President Polk, and according to his own story the colonel remarked: “It is possible we may have some changes in the judiciary.” “Very likely,” replied Davy, “very likely,” and discreetly withdrew. “Well,” he comments, “if I know’d what he meant by ‘judiciary,’ I wish I may be shot. I never heard there was such a thing in all nature.”

Yet another electioneering story attributed to Crockett, shows well enough the rude temper of his region:

“I had taken old Betsy,” says he, referring to his rifle, “and straggled off to the banks of the Mississippi River, and meeting no game, I didn’t like it. I felt mighty wolfish about the head and ears, and thought I’d spile if I wasn’t kivvered in salt, for I hadn’t had a fight in ten days. I cum acrost a fellow who was floatin’ down-stream, settin’ in the stern of his boat, fast asleep. Said I, ‘Hello, stranger, if you don’t take care your boat will get away from you;’ and he looked up and said he, ‘I don’t value you.’ He looked up at me slantendicular, and I looked down at him slantendicular; and he took a chaw of turbaccur, and said he, ‘I don’t value you that much.’ Said I, ‘Come ashore. I can whip you. I’ve been tryin’ to get a fight all the mornin’;’ and the varmint flapped his wings like a chicken. I ris up, shook my mane, and neighed like a horse.

“He run his boat plump head foremost ashore. I stood still and sot my triggers—that is, I took off my shirt, and tied my gallusses tight around my waist—and at it we went. He was a right smart ’coon, but hardly a bait fer a feller like me. I put it to him mighty droll. In ten minutes he yelled enough, and swore I was a ripstaver. Said I, ‘Ain’t I the yaller flower of the forest? I’m all brimstone but the head and ears, and that’s aquafortis.’ Said he, ‘You’re a beauty, and if I know’d yore name I’d vote for you next election.’ Said I, ‘I’m that same Davy Crockett. You know what I am made of. I’ve got the closest shootin’ rifle, the best ’coon dog, the biggest bear tickler and the ruffest rackin’ horse in the district. I can kill more likker, cool out more men, and fool more varmints than any man you can find in all Tennessee!’ Said he, ‘Good morning, stranger, I’m satisfied.’ Said I, ‘Good morning, sir; I feel much better since our meeting—don’t forget about that vote.’”

The story is a trifle apocryphal; yet Crockett himself, in what is called his autobiography, a work which he no doubt dictated, or at least authorized, gives the following account of one of his speeches to a stranger, at Raleigh, while Crockett was en route to Washington to take his first seat in Congress:

“Said he, ‘Hurrah for Adams!’ and said I, ‘Hurrah for hell, and praise your own country!’ And he said, ‘Who are you?’ Said I, ‘I’m that same Davy Crockett, fresh from the backwoods, half horse, half alligator, a little touched with snapping turtle, can wade the Mississippi, leap the Ohio, ride a streak of lightning, slide down a honey locust and not get scratched. I can whip my weight in wildcats, hug a bear too close for comfort, and eat any man opposed to Jackson.’” Which last remark he fain would qualify largely later in his political career! An innate shrewdness that told him how to avoid committing himself was Crockett’s original capital in politics, as it was in life. His native wit, his good fellowship, his rollicking good humor, his courage and strength, his skill with weapons brought him success. He was fitted for success in those surroundings.

One day as Crockett happened to be in a settlement, some forty miles from his home, it was suggested that he run once more for the legislature. He agreed, and forthwith announced himself as candidate. His early methods were again successful. Discovering in himself now certain latent powers whose existence he had not suspected, he later agreed to run for Congress, but was defeated by his late supporter and friend, Colonel Alexander, by the scant margin of two votes. Cotton was high, and Alexander said it was because of the 1824 tariff. Davy did not know what the tariff was, and could not answer!

Crockett at this time is described as a “finely proportioned man, about six feet high, forty-five years of age, of very frank, pleasing and open countenance.” He was dressed in homespun and wore a black fur cap on his head, when seen by a traveler who met him at his house. He now began to show “an unusual strength of mind and a memory almost miraculous.” Uncultured, ignorant, terribly handicapped by lack of training and opportunity, he overcame it all. He got his ammunition from the enemy. He received his sole political education from his opponent’s political speeches, as witness his second campaign for Congress. Cotton dropped in price. Davy promptly found that the tariff argument would work both ways, and he took his advantage. He was elected to Congress, and re-elected, the second victory showing a majority of three thousand five hundred votes.

It is at this stage of his career that we may speak of the birth of the second, or real, David Crockett. These wild surroundings have now begotten in him a rugged sense of self-reliance and a personal independence that henceforth manifest themselves unmistakably. He is a politician, but an independent politician. “I would as soon be a ’coon dog as to be obliged to do what any man or set of men told me to do,” he says. “I will pledge myself to support no administration.” “I would rather be politically dead than hypocritically immortalized,” he declares; and in yet another instance he says that he “will not submit to the party gee-whoa-haw;” that he will be “no man’s man, and no party’s man.”

In spite of all these personal dicta, he is elected. His election costs one hundred and fifty dollars, all in borrowed money. It costs David Crockett, congressman, an additional one hundred dollars, also borrowed, to get to the national Capitol at Washington, where he arrives perhaps the most unique specimen of Congressman ever produced. His first act is to pay his debts—which not all Congressmen since then have done so promptly. It is hard for the backwoods congressman at Washington, yet he has good sense, good tact, good-nature, and a magnetic temperament. His motto, “Be sure you are right, then go ahead,” wins for him sudden fame. Perhaps it is fame too sudden. Now we must bid goodbye to Davy Crockett, bear hunter. He is bitten of the fatal poison of political ambition. From this time on, the record of his life is for a while public, plain, and well known.

Crockett was a Southerner and, as has been stated, at first a friend of the Jacksonian Democracy. Naturally he should have been expected to prove loyal to the doctrines of the South, and the South at that time was held in the hollow of Old Hickory’s hand. Note now a sudden sternness of fiber in the bear hunter’s character that entitles him to a better name than that of time-serving politician. As a matter of conviction and principle, he differs from the autocratic leader then sitting in the president’s chair. He opposes President Jackson’s Indian bill, and the proposition to withdraw the deposits from the United States banks. Indeed, instead of being a follower of Jackson, he comes out boldly as an opponent of his former leader.

The North hails him joyously as a Southerner with a Whig heart. Let Davy make the most of it; none the less he loses the next contest for Congress in his district. Yet he fights again, gets the nomination for the next term, wins once more and hastens rapidly toward the height of a national popularity. Realizing his own ignorance of the North and East, in 1834 he undertakes a journey to those sections. At Baltimore, he sees a railroad for the first time in his life, and witnesses the tremendous feat of seventeen miles made by a railway train in the time of fifty-five minutes!

At Philadelphia, crowds meet him at the wharf and cheer him to the echo. He is banqueted repeatedly, wined and dined times without number, and made the recipient of countless attentions. The young Whigs of Philadelphia come close to his heart when they make him a present of a fine rifle, the very rifle that took the place of “Old Betsy” and was with Crockett in his last fight at the Alamo.

In New York, in Boston, and the larger manufacturing towns of Massachusetts, Crockett repeats his Philadelphia triumphs. He is now a national figure. His sayings and doings are quoted throughout the land. If his Northern speeches are correctly reported, he has at this time suddenly become the possessor of an easy and not undignified oratorical style, though all his speeches are still well sprinkled with quaint epigrams and homely illustrations.

We see in the Crockett of 1834 a figure not approached by any other American statesman so nearly as by that other rugged Westerner, Abraham Lincoln. These crude, virile, tremendous, human men, product of the soil, born of the hard ground and the blue sky - how they do appeal, how they do grow, how they do succeed.

Crockett is asked to visit Harvard College, but refuses for quaint reasons of his own. Andrew Jackson has been made an LL. D. by Harvard, and Crockett says that “one LL. D. is enough for Tennessee.” He is the guest of Lieutenant-governor Armstrong, and chronicles naïve surprise that Mr. Armstrong “did not charge him anything,” for entertaining him. He states that in New England he found “more liberality than the Yankee generally gets credit for.” He expresses his gratitude for the kindly reception accorded him in New England and chronicles his admiration for the thrift and industry of that country, which seems to have made a vivid impression on his mind, different as these scenes were from the wild surroundings in which he himself had grown up.

This trip into the North wrought epochal change for our bear hunter. He learns now about the tariff, studies and approves the doctrines of protection - rank heresy for a Southerner. Deep water for Davy now! He seems to have had no counsel of prudence, for now he loses no opportunity to chronicle his animosity toward General Jackson.

“Hero - that is a name that ought to be first in war and last in peace,” says he. Commenting on the faithlessness of the government, he flames out: “I had considered a treaty as the sovereign law of the land, and now I hear it considered as a matter of expedience.” This was in reference to the treatment accorded the southern Indians by the United States government.

“This thing of man-worship I am a stranger to,” says he, with personal allusion, of course, to Jackson. In all these sayings he is, it may naturally be supposed, heartily applauded by the Northerners, who rejoice in this notable accession to their own ranks.

Davy Crockett, bear hunter and congressman, has now had his chance. He takes himself seriously, even when he jokes about his being the next president of the United States. Crockett represents, now, the success of perfect digestion, of the perfectly normal nervous system. Nothing irritates him. The world to him runs smoothly, as it does to any hardy animal. He cares not for the past and has no concern for the physical future. His big brain, so long fallow, so long unstirred, begins now to fill up with thoughts and ideas and comparisons and conclusions. His reason is clear and bright. He presents to the world the startling spectacle of a middle-aged man educating himself to the point of an intelligent statesmanship, and that within the space of a few brief months or years. He displays a clarity of vision nothing short of marvelous. His memory of names, of dates and data is something startling. The world of books remains closed to him, so that he learns by ear, like a child, but he surprises friends and foes alike. The husk of the chrysalis has been broken. The Westerner has been born into the American!

Davy Crockett had thus far never met any danger of a nature to inspire fear, any difficulty he could not overcome, any hardship he could not lightly endure. He now encountered one enemy greater than any to be met with in the wilderness - that great and menacing foe, the political machine. He found to his sorrow that honor and manhood will not always serve, and at the summit of his success he met his first and irremediable defeat.

Crockett, once the politician, now grown into Crockett the eager student, the earnest statesman, had stirred up animosities too great for him to overcome. The relentless hand of Jackson smote hard upon Crockett’s district. There was talk of money, and of votes influenced by its use. Poor Davy, who went into this last campaign of Congress as blithely and as sure of success as ever in his life, learned that he had been defeated by a total of two hundred and thirty votes! Then there arose from the honest and generous soul of this strange child of the wilderness a great and bitter cry. He was among the first to exclaim against the creed of politics pursued as politics, of statesmanship that is not statesmanship - the creed of party and not of manhood.

“As my country no longer requires my services,” he writes, “I have made up my mind to leave it.” Expressing his determination forthwith to leave Tennessee and to start for the distant land of Texas, he says, “I have a new row to hoe, a long and rough one, but I will go ahead.” He adds as quaintly as ever, “I told my constituents they might all go to hell, and I would go to Texas.

We come now to the third and closing stage of the life of David Crockett, and, in order to understand it, we must bear in mind the nature of the opinions then current concerning the new land that, to the Southerners of that time, was “The Great West,” the land beyond the Mississippi. Texas, a magnificent realm eight hundred and twenty-five by seven hundred and forty-five miles in extent, already had an American population of nearly forty thousand - and, of all wild populations ever gathered together at any place or time of the world, this was perhaps the wildest and the most indomitable. There was hardly a soul within the borders of that great land who was not a fighting man and who had not come to take his fighting chance. It was fate that Davy Crockett should drift into this far Southwest and take his chances also.

As to the chances of it, they were not so bad. It was almost sure that Texas would ultimately be won from Mexico. In 1813 an expedition of Americans had fought Spain and killed hundreds of Spaniards, on the strength of the general claim that the territory of Louisiana extended westward as far as the Rio Grande, and not merely to the neighborhood of the Sabine River, as was claimed by Spain. The latter river was, in 1819, generally accepted as the boundary line, but this fact did not serve to stop the Americans.

In 1823, Stephen A. Austin was settling his Mexican grant with his new colony. These families drew after them the inevitable train of relatives and friends, so that the great River Road to the South and Southwest soon began to be pressed by the feet of many pilgrims. In 1821, Lafitte made his rough settlement at Galveston, and the pirates of Lafitte were no worse than the average Texas population of that time. There were no schools, no courts, no law. One writer states that he sat at breakfast with eleven men, each of whom had pending against him in another state a charge of murder. Then originated the etiquette of the wild West that demanded that no one should inquire into his neighbor’s past, nor ask his earlier name.

In 1833, there were twenty thousand Americans who wished Texas to have an organization separate from the state of Coahuila. They were not so particular as to what government claimed their state, but they wished to organize and run it for themselves. Meeting a natural opposition from Mexico in this enterprise, in the year 1835 they banded their forces, overturned the Mexican government, and set up a provisional government of their own. Henry Smith was chosen provisional governor and Sam Houston commander-in-chief of this wildest of all American republics.

On December 20, 1835, these Texans issued their proclamation of independence, some sixty years after the Declaration of the American Independence. This meant but one thing. Santa Anna, then as much as anybody governor of affairs in Mexico, marched with an army, stated to have numbered seven thousand five hundred men, to besiege the Texans, whose main body was located at San Antonio. No American doubted the ultimate issue. All the South knew that the wild and hardy population of this new region would beat back the weak Latin tenants of the soil. The matter was well discussed and well understood. It was not knight-errantry, therefore, so much as politics, that led Davy Crockett southward into this wild hornets’ nest. Rather should we say that all this movement was part of the mighty, inexplicable, fateful, irresistible Anglo-Saxon pilgrimage across this continent. It was a New World. These new men were those fitted to occupy and hold it.

At this time, the historian of Crockett falls on a curious difficulty. There is published what purports to be an autobiography of David Crockett’s life, a linsey-woolsey affair, made up partly of good English and partly of rough backwoods idiom such as we are accustomed to associate with the speech of this singular man. This “autobiography” purports to be continued after Crockett leaves his Tennessee home for far-off Texas. Yet at this point, its style and subject matter assume such shape as to lead one inevitably to conclude that Crockett did not write it. There are many contradictions and discrepancies, and much of the detailed story of Crockett’s wanderings in the Southwest is denied by practically the only eyewitness of the time qualified to tell of his experiences - that Jonathan H. Greene (the “Harrington” of Crockett’s correspondence), once gambler and later reformed man, who was with Crockett for a time before the Alamo fight. Greene’s story does not in all points tally with the so-called autobiography of Crockett, nor with many of the popular histories of his life.

In general, it may be determined that, with some feeling but without much ado, Crockett said farewell to his wife and family. He had no longer heart for bear hunting. He wished a wider field of life. His journey was down the Mississippi and up the Arkansas River to Little Rock. There he encountered many hail-fellows-well-met, and had several experiences, which are set forth at length in his autobiography. He journeyed then horseback to Fulton, descended the Red River to Natchitoches and then made his way westward across Texas.

The so-called autobiography of Crockett describes two or three strange characters: the “Bee Hunter,” who might have been the hero of an English melodrama of the time; “Thimblerig,” the sharper whom Crockett reforms and leads on to die a hero’s death; the “Pirate,” who dies in front of the Alamo gate; and so on. There is something strangely unreal in much of this. It does not ring true. Yet we are further told that Crockett crossed the Sabine, that he met the Comanches, that he saw for the first time the tremendous herds of buffalo, that he encountered bands of wild horses, that he saw much wild game, and, in a knife fight, killed a panther. The feeling is irresistible that many of these pictures are made to order.

At last, however, we find Crockett inside the gates of the San Antonio barracks, one of that little party whose heroic death was to set the whole American nation a-throb, first with vengeful fire, and then with a passionate love and admiration.

The situation was thus: Travis in San Antonio, practically hemmed in at the adobe building known as the Alamo; Fannin at Goliad, with other noble fellows later to fall victims to Mexican treachery; at a distance Sam Houston, apparently irresolute and non-committal. Austin, Fannin, Travis, Rush, James Bowie, the Whartons, Archer of Virginia - what a list of strong names was here, these fighting men, some of whom had come for politics, some for sport, some for sheer love of danger and adventure. Of these, Bowie, Crockett, Fannin, and Travis might have been declared opposed to the party of Houston and Austin. Crockett’s authentic letter bitterly accuses Houston, the leader of the Texans. Houston, mysterious, vain, enigmatical, as able as he was erratic, might perhaps, had his followers been less tempestuous and independent, have united them into a harmonious and powerful whole. He could not - or did not. Hence came the Alamo fight.

Of this wild army, half ruffian, half adventurous, most of the men were poor, although they came in many cases from good families. They had behind them an undeniable sentiment in favor of the independence of Texas, and were backed by money raised for that purpose. General Jackson openly and notoriously favored the annexation of Texas, and perhaps even of Mexico, and went so far as to suggest a few practical though unauthorized plans of his own as to how the army might be used to bring about a conflict and later a pax Jacksonii. Thus, we find our hero, Davy Crockett, once more falling into the plans of his former chief, his recently victorious antagonist, Old Hickory.

It is possible that Crockett was deceived in his pilgrimage to Texas. There is more than a suspicion that he was used as a cat’s paw in a political movement. He says that “Houston is enjoying the support of the Government, while others are left to do the fighting.” He continues, “Houston has dealt with us in prevarications.” He calls Houston the “agent” and Jackson the “manufacturer.” Yet, certainly, Crockett was backed by a prevalent and strongly growing sentiment. The records are too vague and insufficient. We shall never fully understand all these complications of early and adventurous politics.

Be all these things as they may, Crockett was one of the devoted little band of a hundred and eighty-three Texans, who in time found themselves besieged by an army of Mexicans from five thousand to eight thousand strong. The peons of Santa Anna’s army came on day after day, the bands playing the Dequelo, which meant “no quarter.” For eleven days the Texans held the Alamo, in that historic fight whose details are so generally and so uncertainly known. These one hundred and eighty-three men killed of the enemy more than one thousand. Worn out by loss of sleep and continuous muscular exertion, their arms simply grew weary from much slaying. Their hands could no longer push down the ladders weighted with the struggling peons goaded forward by the swords of their officers.

At length an assault was lodged. The swart Mexicans, more in terror than in exultation, poured across the broken wall. In the hospital lay forty helpless men, each with his rifle at his side. These, sick and crippled, broken-bodied, iron-hearted, poured their last volley into their assailants as they came in. A cannon was discharged down the room and nearly a score of the crippled and sick were blown to pieces. Outside, in the open space, the lances of the Mexicans reached farther than the clubbed rifles or the bitter, biting knives of the stalwart Americans, now raging in their last tremendous, magnificent, and awful Baresark rage.

No one knows the story of the end. Even the number of the victims is matter of dispute. Some say there were a hundred and eighty-three defenders, some say a hundred and eighty-six. Some say one woman escaped, some say two. Some declare that one negro servant got away, some say two. The state of Texas adopted the “Alamo baby,” but the Alamo baby did not see Crockett fall. There are different reports. Some state that there were six Americans left hemmed up against the wall, and that the Mexican General, Castrillon, called upon them to surrender. They did so, Crockett being one of the six. Confronting the Mexican commander, they were treacherously ordered to be shot down. It is said that Crockett, bowie knife in hand, sprang with all his force for the throat of the Mexican general, but was cut down or shot down with the others, “his face even in death wreathed in an expression of contempt and scorn at such treachery.”

All this is but imagination; and there is all reason to suppose that there never was any surrender of these six last survivors. The common story is that Crockett fought to the last with his broken rifle, and was killed against the wall - before him lying the bodies of some twenty Mexicans. The usual impression is that he killed these twenty Mexicans himself before he was cut down, but this is perhaps the result of emotional writing. No one knows how many foes had fallen to his arm. No one can tell how many Mexicans each of these raging, fighting men destroyed before he himself went down. Earlier in the siege, Crockett recounts picking off five cannoneers one after the other. He tells how the Bee Hunter and Thimblerig did their sharpshooting, how the Pirate died of wounds received in a sortie, how the Bee Hunter - a most unlikely thing - burst into poesy and song at the hoisting of the Texas flag. Some of these things have too unreal a sound. There is something not quite Crockett, though à la Crockett, in the conclusion of Crockett’s so-called, or rather alleged, diary:

“March 5 - Pop, pop, pop! Bom, bom, bom! throughout the day. No time for memorandums now. Go ahead. Liberty and independence forever!”

These are the last recorded words of Davy Crockett. It is probable in the extreme that he never wrote them. It is unlikely to an equal degree that, in all the turmoil of the Alamo fight, he could deliberately have kept a diary, or that it could have been preserved after all the horrible details of that bloody and disastrous conflict. As to the end of Davy Crockett, there is and has been no living human being who could speak with absolute accuracy and authenticity. Bloody San Jacinto, the field where the cry “Remember the Alamo!” was the watchword of a dire and just revenge, left but few Mexican eyewitnesses of the Alamo.

Be that as it may, we know that Davy Crockett died fighting, that he died with his face to the enemy, like the brave man that he was, undaunted, unafraid. No politics now, no statesmanship, no little ambitions now for Davy Crockett. He was once more the child of the wilderness, stark, savage, exultant, dreadful, one more of those titanic characters that swept away a weaker population, beat down all opposition, conquered the American wilderness, and made way for an American civilization.

The study of Crockett’s life shows us an America yet loose and scattered, not knit together into a national whole - and the political problems of that day were still those arising from geography. Backwoods Davy was, after all, not so poor a thinker, nor so far from getting to the marrow of things. After his visit to the North, and his reconciliation to the doctrines of a protective tariff, he makes one comment which, while it may not settle political argument, ought to teach a national courtesy and a human tolerance on both sides in any national difference.

“If Southerners would visit the North,” he says, “it would give different ideas to them who have been deluded and spoken in strong terms of dissolving the Union.” A trifle ungrammatical this, perhaps, but startling reading, when one remembers that it was recorded in 1834. Again, we find our independent thinker discussing freely the questions of transportation, which were then and always have been so important in this country. He was opposed to Jackson in the first place because Jackson “vetoed the bill for the Maysville road.” He was opposed to Van Buren because he “voted against the continuance of the national road through Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, and against appropriations for its preservation.” He opposed Van Buren further because he “voted in favor of toll gates on the national road, demanding a tribute from the West for the right to pass on her own highways, constructed out of her own money, a thing never heard of before.”