A Model Squadron of the United States Cavalry - circa 1894 (Historical Reprint)

Historical article reprinted from the book "Pony Tracks" written & illustrated by Frederic Remington in 1894.

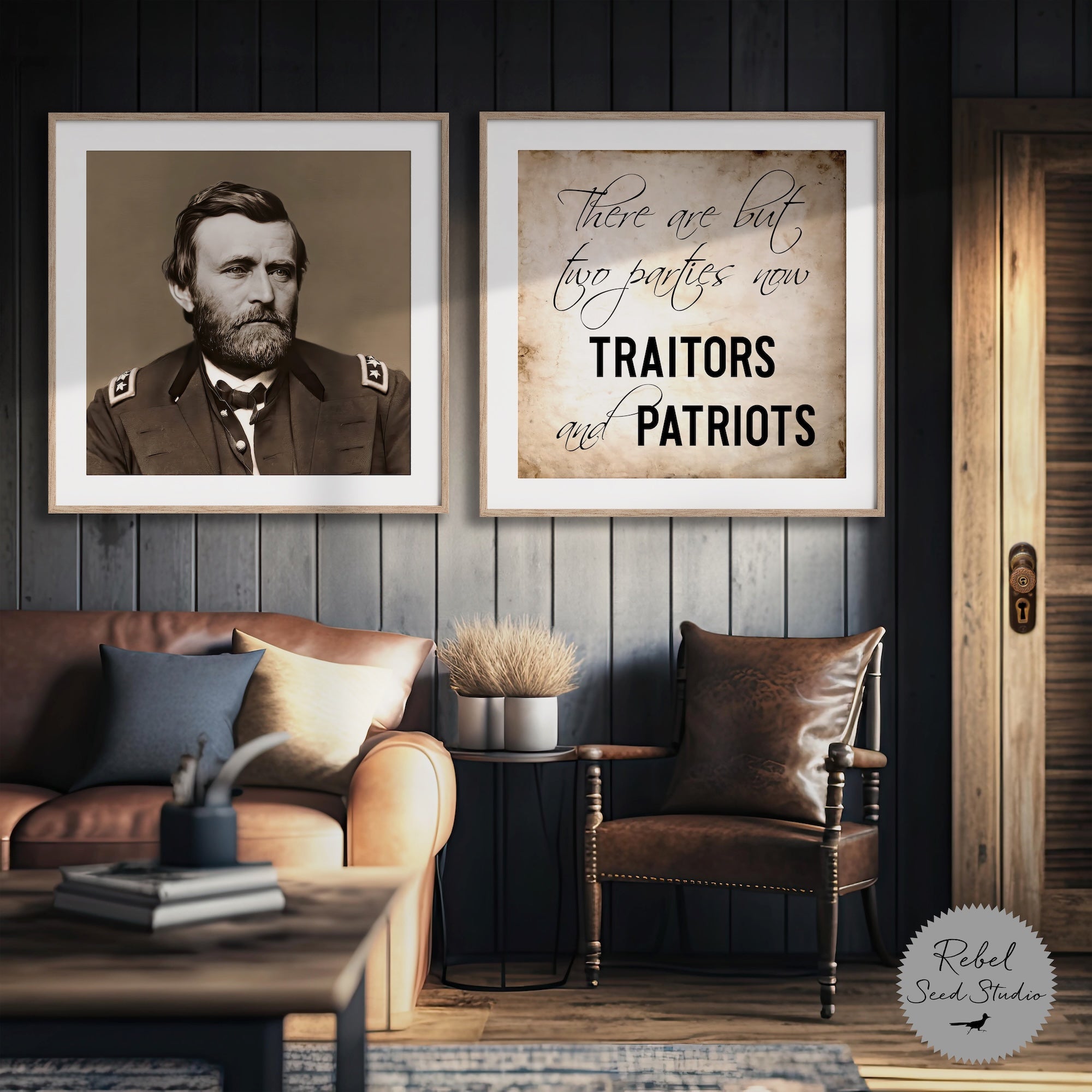

I am not quite sure that I should not say “The Model Colonel” since every one knows men and horses are much alike when they have first passed under the eye of the recruiting officer and the remount board, and every one knows that colonels are very unlike, so that a model squadron or a model troop is certain to owe its superiority to its commander, but as we are observing the product in this instance, let the title stand as above stated.

The model squadron aforesaid is quartered across the Potomac from Washington in Fort Meyer, which is the only purely cavalry post in the country. Everywhere else the troops are mixed, and the commandant may be of any arm of the service. Here they are all cavalry, with cavalry officers and cavalry ideas, and are not hindered by dismounted theories, or pick-and-shovel work, or any of the hundreds of things which hamper equally good “yellow legs” in other posts. There are many passable misdemeanors in this post, but only one crime, and that is bad riding. There is little dismounted work, and any soldier can have his horse out on a pass, so long as he does not abuse the privilege - and when he does, it’s plenty of walking falls to his lot.

There is a large brick riding-hall of approved pattern, which enables the men to do their work in all weathers. The four troops now quartered there are from the First, Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth regiments, which creates a good-natured rivalry, very conducive to thorough work. It is the opinion of General Henry that one old troop should always be left at this post as a pace-setter for the newly transferred ones, which seems reasonable.

Illustration: General Guy V. Henry, 7th U.S. Cavalry

Now to tell what the preparatory discipline is to the magnificent riding, which can be seen any morning by spectators who are “game for a journey” to the fort by ten o’clock, I must say that General Guy V. Henry is a flaming fire of cavalry enthusiasm. He has one idea - a great broad expanse of principle - ever so simple in itself, but it is basic, and nothing can become so complicated that he cannot revert to his simple idea and, by it, regulate the whole. It is the individual training of the horse and rider. One bad rider or one unbroken horse can disarrange the whole troop movement, and “woe to him” who is not up to concert pitch! “Who is the scoundrel, the lummux, humph?” and the colonel, who is a brevet-brigadier-general, strides up and down, and fire comes from his nostrils. “Prefer charges against him, captain!” and the worst befalls. The unfortunate trooper has committed the highest crime which the commandant of Fort Meyer knows -- he cannot ride.

A soldier becomes a rider by being bucketed about on a bareback horse, or he dies. The process is simple, the tan bark soft, and none have died up to date, but all have attained the other alternative. This is unimportant; but the horse - it is to his education that the oceans of patience and the mountains of intelligence are brought to bear. It is all in the books if any one cares to go into it. It is the gathering of the horse. It is the legs carried to the rear of the girths. It is the perfect hand and the instant compliance of the horse with the signs as indicated by the rider. It is the backing, the passaging, the leading with either foot, and the pivoting on the front legs. It is the throwing of horses, the acquisition of gaits, and the nice bitting. It is one hundred little struggles with the brute until he comes to understand and to know that he must do his duty. It all looks beautifully simple, but in practice we know that while it is not difficult to teach a horse, it is quite another matter to unteach him, so in these horses at least no mistakes have been made.

After all this, one fine sunny Friday morning the people drove out from Washington in their traps and filed into the galleries and sat down - fair women and brave men - of the former we are sure, and of the latter we trust. The colonel blew a whistle (ye gods, what a sacrilege against all the traditions of this dear old United States Army!) and in rode Captain Bomus’s troop of the First Plungers, which I cannot but love, since I am an honorary member of their officers’ mess, and fondly remember the fellows who are now sniffing alkali dust down in Arizona. They were riding with blankets and surcingles, and did their part of a drill, the sequence of which I have forgotten, since it was divided with the three other troops (Captain Bell’s of the Seventh, Captain Hughes’s of the Ninth, and Captain Fountain’s of the Eighth.) I felt a strong personal interest in some of these men, for memory took me back to a night’s ride in Dakota with a patrol of the Ninth, when they were all wrapped in buffalo-skin overcoats, with white frost on their lapels. The horses’ noses wore icicles, and the dry snow creaked under the tread of the hoofs as we rode over the starlit plain and through the black shadows of the coulees. I had pounded along also through the dust in the wake of this troop of the Eighth when it wasn’t so cold, but was equally uncomfortable.

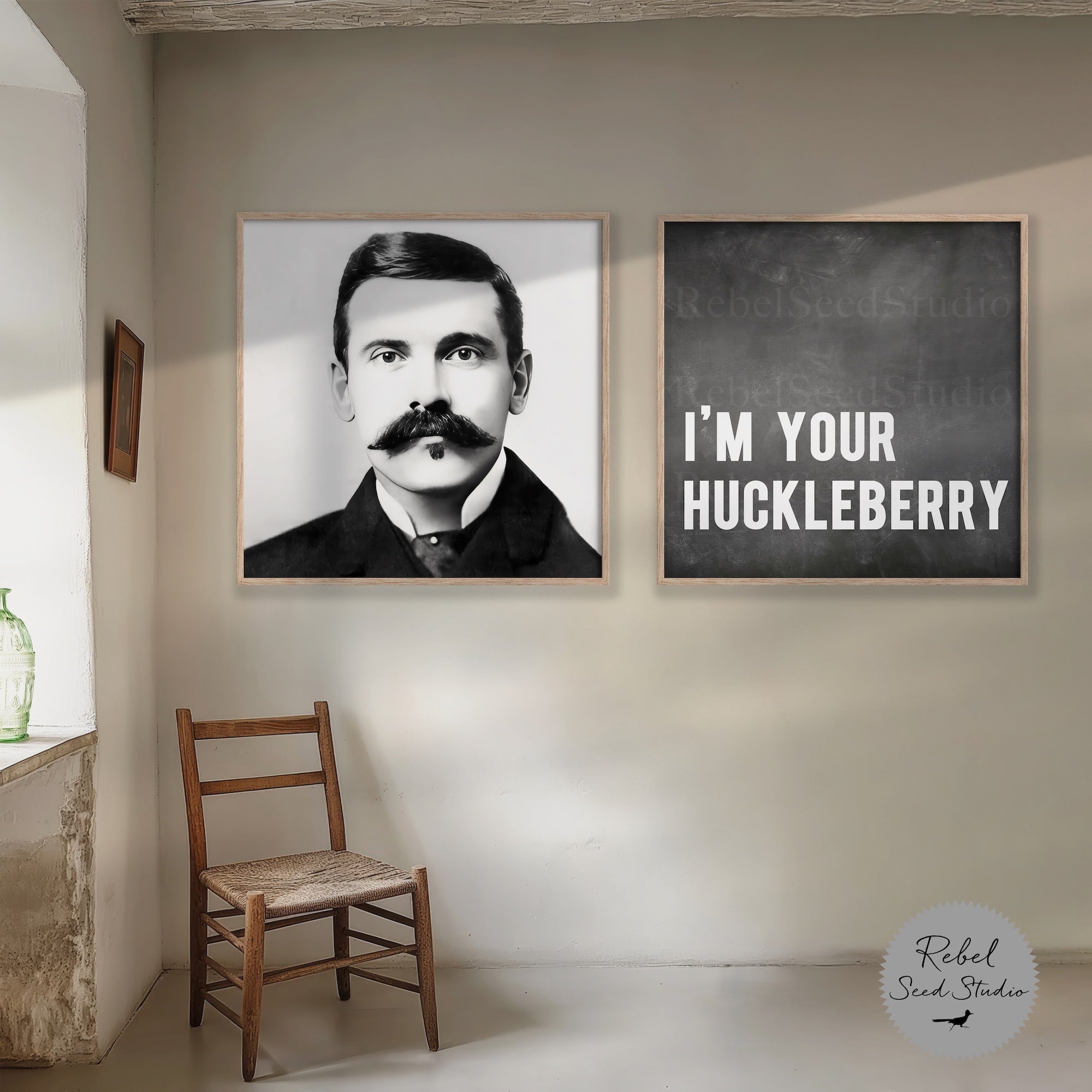

Illustration: Riding Sitting on Legs

The sharp commands of the captain soon put the troop in motion, and they trotted along with a cadenced tread, every man a part of his horse. They broke into fours and wheeled to the right about, then into line and wound themselves up in the “spiral” and unwound again, and soon brought order out of a mess, and the regular canter was ever the same. Then low hurdles were strung across the hall, and by column off ours the troop went over, never breaking the formation. To the rear they turned and back again. Finally, they took the obstacle in line, and every horse rose as though impelled by the same mechanism. As if this was not enough, every second man was dismounted and put on double with a comrade, not with his breast to his comrade’s back, but back to back, and then in line the odd cavalcade charged the hurdles, and took them every one. It was not an individual bucketing of one horse after another, but all in line and all together. After this, what could there be more to test the “glue” in these troopers’ seats? There was more, however, and in this wise: The saddles were put on, but without any girths, and all the movements were gone through with again, ending up with a charge down the hall, and bringing up against the wall of the spectators’ stand at a sharp “halt”, which would have unseated a monkey from a trick-mule.

The horses were all thrown by pulling their heads about, and one cavalryman amused himself by jumping over his prostrate mount. They rode “at will” and stood upon their knees on their horses’ backs. One big animal resented carrying double, and did something which in Texas would be called “pitching” but it was scarcely a genuine sample, since the grinning soldiers made little of it. The troop of the Ninth executed a “left backward turn” with beautiful precision, and this difficult undertaking will serve to give one an idea of the training of the mounts.

Gymnastics of all sorts were indulged in, even to the extent of turning summersaults over four horses from a springboard. A citizen near me, whose mind had probably wandered back to Barnum and Bailey, said:

“But what’s this got to do with soldiers? Is it not highly flavored with circus?”

Illustration: Over the Hurdle Back-to-Back

I could offer no excuse except the tradition that cavalrymen are supposed to ride well. All the men were young and in first-rate physical fix, and seemed to enjoy the thing - all except one old 1st sergeant, who had been time-expired these half-dozen times, whose skin was so full of bullet holes that it wouldn’t hold blood, and who had entered this new régime with many protests:

“O’me nau circus ape. I can’t be leppin’ around after the likes avthim!” where at the powers arranged it so that the old veteran got a job looking after plug tobacco, tomato cans, tinned beef, and other "commissaries” upon which he viewed the situation more cheerfully.

The drill was tremendously entertaining to the ladies and gentlemen in the gallery, and they clapped their hands and went bustling into their traps and off down the road to the general’s house, where Madam the General gave a breakfast, and the women no doubt asked the second lieutenants deliciously foolish questions about their art. The gentlemen, some of whom are Congressmen and other exalted governmental functionaries, felt proud of the cavalry, and went home with a determination to combat any one hostile to cavalry legislation, if a bold front and firm purpose could stay the desecrating hand.

But all this work is primary and elementary. The second degree is administered in field work, comprising experimental marches, and those who know General Henry by reputation will not forget his hundred-mile march with the Ninth Cavalry at Pine Ridge, and those who know him personally will become acquainted with his theory that a cavalry command in good condition, with proper feeds, should make 50 miles a day, with a maximum on the road of 10 hours a day, moving at the rate of five miles an hour in cavalry halts, the gaits being walk, trot, and leading, with a day’s rest each week, to be continued indefinitely. And knowing all this, they will be sure that the model squadron wears out a good many horseshoes in a season.

Illustration: Throwing a Horse

The “Cossack outposts” are another feature much insisted on, and, strange to say, this arrangement was first invented in America, despite its name, and is an improvement on picket posts in a ratio of 240 to 324. Another movement is the “form square” which is an adaptation of the “Indian circle” it being a movement from a center to a circle, and useful when escorting wagons or when surprised. The non-commissioned officers are sent on reconnaissance, on patrols, and are required to make maps, which are submitted to an inspector.

Another scheme which I have never seen was the linking of a troop of horses, formed in a circle, to one another, by hooking the regular cavalry links from one horse’s bridle to the next one’s halter ring, and then leaving them in charge of one man. I also saw the new cavalry bit for the first time. It is commended by all who use it, and I saw no horses boring on it or in the least uppish about going against it, and I never remember a horse who would not do either the one or the other to the old trap which was formerly worn.

Two other curious movements indulged in by this squadron are the firing over horses while they are lying down, and riding double - the man faced to the rear draws his pistol, and while moving to the rear keeps shooting. It might be useful during a slow retreat, and could be done with the carbine equally well.

This whole enterprise at Fort Meyer is vastly encouraging. As one officer said, “We take no credit for it, since others could do the same if they had riding-halls and cavalry officers in command.” But there are cavalry officers and there are cavalry officers, and it is not every day one is born. For 35 years has the old general sat in a McClellan saddle, and the tremendous enthusiasm of newly joined “sub” still remains. The very thought of a wagon arouses his indignation, and every day the mules are brought into the riding-hall, and the men initiated into the intricacies of the “diamond hitch.” It takes a past-master to pack a mule in 22 seconds, however, and I saw that feat accomplished in General Henry’s command.

It is a grand thing for the young men to have this practical training by these old veterans of the civil war and the alkali plains before they go on the retired list. It is well for a young man to know enough not to unsaddle a sweating troop of horses in a broiling sun, and to learn that it makes sore backs. And it is quite important if men can cook rations, and not go up to the skyline of a hill when scouting, and rival the statue of "Liberty Enlightening the World” when it is clearly their business to throw what light they have behind them and not before. It takes experience to put the sole of a boot back on the upper, when it has fetched loose, with four horseshoe nails, and it is not every man who knows that the place to intrench is on the edge of a cut bank, near water, if one expects ever to get out of a round-up.

No one can figure that a recruit will know how many people passed over the road before him, or which way they were going, and it takes a longhead and good nerves not to pull a trigger unless the sight is dark on the object when the fight may last all day and probably all night, but all these things are not taught in school. If a horse under him is weakening on a long march in an enemy’s country, it is an ignorant fool who uses a spur instead of good sense. That’s the time to unload a few dollars’ worth of government property. But who can understand the value of a rubber blanket, fifty rounds of ammunition, and a pocket full of grub, with a feed of grain in the bag, but one who has tried it? There are lots of dead soldiers who would have learned these lessons if they had been older. In my opinion, the tremendous box of tricks which Uncle Sam’s horses are supposed to carry has put more men afoot than will ever be admitted - but at least the old boot has gone, though there is yet room for an intelligent hand with a jack-plane to shave off that cavalry pack. I am inclined to take what every one tells me is a “cranky” view on this subject, but let it stand until the next hard campaign, and I hope to be able to be more lucid. Horses are horses, and horses are not made of wood, iron, or by rule of thumb.

To revert to Fort Meyer: it is altogether refreshing; it is worth anyone’s while to go there and see four troops of cavalry which cannot be beaten, and it is positively exhilarating to meet their creator, a thoroughly typical United States cavalry officer, and I’m bound to say his successor in command has had a hard pace set for him.